Tuesday, June 30, 2009

Interview with Pierre MacKay: Part 3

You’ve made several comments that indicate the School was in dire straits financially during your Regular Year. Was it an issue that weighed on everyone? I don’t think as students we were adequately aware, but the School went through a near crisis. And then people like McCreadie and Williams and a lot of non-Academics who were devoted to the School revamped the Board of Trustees and they did a fundraiser that was just spectacular. By the end of it there was this sudden explosion of fellowships, which the school had never been able to offer before.

When was this? In the 70s. What do you mean ‘revamping’? I don’t know how the old Board of Trustees worked, but I can kind of guess that it was a New England and East Coast club with occasional reliance on hugely generous donors. For instance, the first Annex to the library was pretty well a personal achievement. The Gennadion was Rockefeller money. And I think there were huge donations by other people, but that’s so chancy. In the aftermath of the Second World War, when a lot of Classics departments closed down, when they started up again the American School no longer had the ties to the universities so it had to be completely redeveloped. And I have great admiration for the people who re-established the refinancing of the school. I gather the present economy is causing a little worry, but I bet it’s nothing like that one in 1970s.

You just mentioned that a lot of Classics departments had closed down or went defunct in WWII. What was that scenario? Well, people went off to war. There were things the universities had to do. And the University of Washington Classics department essentially ceased about 1943 and started up again when John McDiarmid came to re-create Classics in the University of Washington. There were many, many universities where the same thing happened. It was just not seen as a priority. And a lot of the School faculty went into the intelligence services. There are very funny stories of Sterling Dow and his contemporaries trying to decide to mark a railway on a map of Bulgaria as ‘completed’ or ‘not completed’ or ‘useful’ or ‘not useful’. Sterling Dow was a visitor the second year we were here and he was splendid. A splendid person to have around. Sterling would quite openly talk about the intelligence side of his war-time years. Every once in a while we’d be sitting on a hill on the old Thebes-Athens road and a convoy of military vehicles would come by and Sterling would say, “Now, how would you estimate the size of the troop contingent going by and what is it intended for?”

It hadn’t been that long before you came that WWII ended. Were there a lot of people around who had been involved in the War in Greece? A lot, a lot. Vanderpool had spent two, two-and-a-half years in a concentration camp because he’d insisted on staying in Athens. [Bert Hodge] Hill somehow managed to browbeat the German authorities so completely in Corinth that they let him alone. This is getting off the history of the school, but it is part of the whole history of Classics, not merely here but in Western Europe generally: there were a whole lot of people whose education was generally, essentially, shut down by 1941 and who came through the War and when they decided what to do at the end. They KNEW what they wanted to do, they weren’t uncertain; they KNEW it because they’d thought about it. I think it produced a generation of scholars, and not only in academics - there were all sorts of developments in new music by people who had been kept silent for six or seven years and had not had to waste their time on the concert circuit and who had thought about what they wanted to do. So it was on the British and the American side: Bernard Knox, Angie Hammond, and people who were very tight-lipped about it, like Bradford Wells in Yale who was the head of Cairo Station during the war (though you’d never learn it from him). Virginia Grace was very active in the intelligence service. So many of these people.

Did they talk about it a lot? It all depends on who you were talking to. You almost couldn’t shut Bernard Knox up about it, he had so much fun. His war was real fun. Of course, he started out early – he described his adventure into the Spanish Civil War as “six weeks running away from Franco and six months running away from my own side.” But he ran a bunch of partigiani in north Italy. He had the time of his life. Sterling Dow was a homebody but he got lots of fun out of it. Brad Wells, now. One of the reasons Brad Wells couldn’t really tolerate Bernard Knox was that when Brad Wells was told to destroy his papers, at the end of the war he did so and he never spoke about it again. Of course, Bernard was ALWAYS talking about it! He gave me instructions on where to put the charges if you were blowing up a bridge and you didn’t think you had quite enough explosive to do it with complete efficiency. It was apropos of nothing at all. There were so many of them [who’d been involved].

You said that you left in ’61? Do you know what impact Vietnam had on the community here at the School? No, I don’t. That’s when I really lost touch with the School. I was in Egypt ‘64-5, Turkey ‘65-6, and then moved out to Washington. I was so involved in Arabic and Turkish at the time that I sort of lost touch with the School to a very large extent.

You said that you were the token Byzantinist during your Regular Year - we still have some of those. What was it like being that, since there was probably even less interest in Byzantine Greece at that time period? Well, I had gone through regular Classics courses. I had not come out of a history department with minimal experience in Greek. I had taken the full requirements of a Berkeley PhD, which meant I had taken a lot of Greek. It should have meant I’d taken a lot of Latin, but my father was my graduate advisor by an accident of personnel. I suggested to him that the rules of the university said that a PhD student at the university should have a competence in two classical languages, and I said, “does that mean classical Arabic?” and he said, “Well, I don’t see why not.”

What was your dad doing at that time? He was a Latinist, although I had a feeling that he never really wanted to be one, but that was what was available when he got his position. And then he was called down from Vancouver to Berkeley to become Chairman of the Department there. So you’d already had some Arabic when you came to the American School. Was there a happy rivalry between the Classicists versus the Byzantinists, ‘cause we always make fun of our token Byzantinists about it (in a loving way of course)? Well, they didn’t know where I belonged. All my official credentials were in ‘Classics’ Classics. My interests seemed a bit bizarre. I could hold my own in Greek prose with most of the people here.

Were there a lot of archaeology or art history kids that had come over? Darn little art history. There was a lot of the formal Bryn Mawr style archaeology. How many Bryn Mawr students did we have? Theo…I think Ione was Bryn Mawr. Anyway, it tended to be pot-people, sculpture-people and people who wanted to lead an excavation, like Joe Shaw who made quite something of it. It was an extraordinary year. The list just goes on and on and on.

You said you went a different direction after your Regular Year and before coming back to the School. When did you come back and what were the circumstances? I’d retired and I went through 5 years of part-time re-hire and I was bound and determined that I would try for the Whitehead [visiting professorship], and I got it!

What was your Whitehead seminar on? I saw the students and I said, “The thing I see in this body of students, is there are very few people who have had adequate time in Greek,” so I did a site reading seminar in Greek. I thought it was more important than any sort of esoteric thing that I could involve them in. The fun of the site reading was that we did one of the Lysias speeches about the aftermath of the democratic restoration, which involved a man who claimed to be a democrat; he was up in the mountains at a steep site. Everyone crowded around him and said, “I know what that man did, that man is NO friend of the democracy.” They grabbed him and dragged him across to where there's a steep cliff and said, “What we really ought to do is throw you off right here.” And just after having read that description in Lysias we went up on to the mountain. It was great fun.

Was that when you lived upstairs in Loring? Oh, the brief time of living upstairs was when by shear accident at a conference in Istanbul, I heard about a conference for Medieval Chalkis run by the Hellenic Institute of Venice. I had just come very close to the conclusion that what we were looking at there in Chalkis was the Dominican Priory church, so as soon as I heard about it, I wrote to the Hellenic institute and said I had several things I could do on this subject. Fortunately, they said I should do the Dominican topic, which I did with some hesitation because I was proposing an identity for the building which had never been proposed and which meant it was NOT a Byzantine monument, in any sense whatsoever. And then Nikos Delinikolaos, the restoration and conservation archaologist, who oversaw the reroofing and the cleaning up of the walls, sent me his paper, and in one of his illustrations was St. Dominic on one side and St. Peter on the other – WHOOPEE! So I went there and focused my paper to say, “If you don’t believe this, wait ‘til my colleague presents!” Oh, it was wonderful. He said afterwards that he had the same feeling I had, that the hostility he was going to get there was such that he wasn’t quite sure he wanted to present. But the two of us together had a tremendous time. And so I was just here in Athens for a few days, which was when I got to use the ‘Queens' Megaron.’

When was that? 2001-2002. When were you the Whitehead? 2002-3. What would you say is most striking about what has changed and what has stayed the same here at the School? Well, the thing that’s the same and what I absolutely support is the system of four trips in the fall. I just think that no other foreign archaeological school does this; particularly for people coming over from the other side of the Atlantic it is sooo important. Even people who could afford a private car would never see the things we got to see. Other than that, well, this time around I can’t get over to the Teas and Ouzos much, but they’re pretty much the same as they used to be. So, the basic structure of the day is still the same, and good. The staff is immense compared to how it used to be.

Well, thank you so much, Pierre, for sharing your stories with us. It’s lovely to be reminded of them.

Saturday, June 27, 2009

The Burbs of Athens

Dallas DeForest, Brian Swain and a complete stranger gaze at three sarcophagi, thought to be those of Herodes Atticus’ children, buried by their father. They're kept behind glass, right next to a periptero (kiosk) and amongst all the Kifissia shopping.

Menander: "A rich wife is a burden. She doesn't allow her husband to live as he pleases. Nevertheless, there is one good to be gained from her: children."

More recently, Kifissia has been home to political dynasties and the mansions that they build, as well as a succession of ritzy shops and cafes. It doesn’t have quite the glitz and bling of Kolonaki. Whereas Kolonaki is sorta South Beach, Kifissia feels a little more like West Palm Beach, to me at least. Others might think Cape Cod instead, with its ‘old money.’ The Nazi’s used the Kifissia home of Panayotis Aristophron, who excavated Plato’s Academy, as their invasion headquarters.

There’s not much ancient stuff left to be seen these days, even if you do wander around with a copy of Tomkinson’s Athens: The Suburbs, nicked from your professor’s shelf. The Church of the Panagia, supposedly built with the blocks of Herodes’ villa, is fenced off and locked. The Grotto of the Nymphs, used by women for divinatory purposes up until the 19th century (Tomkinson p.54-5), can’t be found by visitors.

At least, it’s lost to us. Brian and Dallas in Kifissia’s Kokkinara ravine, where we found garbage, dead birds and thorns, but no Grotto of the Nymphs.

It was Melissia, however, that proved to be a much more interesting ‘hood than Kifissia. Although it’s well-to-do, it doesn’t put on quite so many airs as Kifissia. It has shady lanes and plateias (squares), feels like it’s not trying so hard to impress rich people and teenagers, and appears to have a hefty sense of local identity.

Apparently the town was settled by Pontic Greeks sometime in the 20s after the ethnic cleansing in Turkey (I’d be more exact with my details if someone would be kind enough to fix Melissia’s Wikipedia article.) That's when, thanks to the now divinized Ataturk, the burgeoning nation of Turkey felt the need to expel all non-Turkish/non-Islamic elements. This included Greek villages whose ancestors had settled the region as early as 800 BCE – I guess in Turkey at that time you’d had to be around for more than 2,800 years for squatter’s rights to apply.

Anyways, in the 19-teens and early '20s, Pontic Greeks, Armenians and many others were the victims of genocide, were massacred or were forced to leave their homes. Think the ethnic cleansing of the Indian Removal Act or, as we more commonly call it, the Trail of Tears.

So all the Greeks in Turkey had to go back to their ‘true home’ in Greece. A group settled in Melissia, small town at the time, but now engulfed by the sprawl of Athens. The EU has even given money so that the neighborhood can spruce itself up a bit with better drains, nice cobble walking paths, and some fancification for its charming, shady, Plateia of the National Uprising.

The sculpture, paid for by a local patron, celebrates the mountain klefts who resisted the Turks and who represent the idea of Romiosini. We had a nice dinner in the beautiful plateia last night.

Melissia sits right at the edge of Athens. And I mean ‘edge’ because on one side of the Plateia is the city, and on the other side is the countryside. On Thursday Dallas and I wandered out that way to hike up Mt. Penteli.

Just a few years ago, the hills north of Melissia were covered in trees, but the 2007 forest fires have left behind a barren, charred wasteland. I couldn’t help wondering if anyone had been up to do a survey on Penteli since the fires, since we could see field boundaries and roads in all directions. It’s pretty stunning to see the view from Google Earth:

One of the more interesting things we came across was a glittering cemetery out in the middle of nowhere. It’s the cemetery of Melissia, with specific hours of access, a church and a lone desolate bus station.

The earliest death noted on the tombstones was 2003, so it seems to be a more recent cemetery. Oddly, though, parts of it were totally trashed, with shattered marble crosses and other grave paraphernalia in distinctly seperated areas.

New terraces were under construction. We watched a grave digger with a pick ax, working amongst rows of new, empty graves. He looked like nothing more than an archaeologist, actually. Given the relative dates on the ruined graves and the well-formed, marble ones, Dallas suspected that the cemetery had been destroyed in the fire, and the town was slowly fixing it up. None of the preserved marble fragments bore signs of fire, but that's the most likely idea we could come up with.

It was a strange place. The cemetery was also the parking area for the town’s municipal trucks and blue trash bins; it had the distinct appearance of a work site. The church was in the Neo-Byzantine style so common to Greece nowadays and was utterly immaculate. And the graves, one after another, bore birth years in the 19-teens and '20s. Can it be that this incongruous burial ground was the resting place of the Pontic Greek children exiled from their ancestral homes? We asked our Melissian sources but found no answers.

Perhaps when the area was wooded it didn't seem quite so eerie and out of place. Whatever its story, the town of Melissia is pretty concerned with keeping the graveyard well-maintained, even if it is visibly tucked away and hidden. It's nice to see a town that is so actively holding on to its own local history, one that is more modern than ancient.

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Ptoo, ptoo, ptoo

Like in many parts of the world, one of the dangers lurking in Greece is the evil eye. Tourists are bombarded with sales pitches and trinkets to protect them from what is advertised as a quaint local custom. I never really quite figured out what the evil eye was - I assumed somebody just gave you a nasty look, the kind of nasty look that could do some serious damage. Working in the trenches in Corinth has given me a new appreciation of the sorts of dangers that lurk here, however, the evil eye being one of many.

Over the last few weeks, I spent a lot of time at the dry sieve with Vassilis, our barrow-man. He taught me a lot of Greek excavation words, as well as some Arvanetica (Albanian), since many Greek towns, his included, have populations that speak a mixture of Greek and Albanian. I also learned that yawning is a sign of the evil eye...Okay, so I yawn a lot on some days – it’s the teenager still hidden within me. For a while Vassilis and I had a back and forth infectious yawn-thing going, which he always laughed at but which he said meant I was spreading the evil eye. In Greece, it’s called the Mati. If I yawned, Vassilis would say in mock seriousness, “Katie, Mati! Mati, Katie!”

The Mati, I learned, can be caused if people are concentrating on you too much, even if it’s in a positive way. As Katerina Ragkou (our water-siever) just put it, if someone thinks about another excessively because, say, they like them too much, or are envious of them in an admiring way, or if they think many negative thoughts about them, an enormous amount of energy is focused on that particular person. Apparently no one can handle that much directed energy and a person’s body just plain gives out – they feel nauseous, exhausted, and inexplicably ill.

Even though Vassilis would joke about my Mati, he still made the ‘ptoo, ptoo, ptoo’ noise (the fake spit) when it came up. He did it so often that by the end of my two months at Corinth, all Vassilis had to say was ‘Katie, Mati!’ and I was ptoo, ptoo-ing over my own shoulder to keep him satisfied. Unfortunately, if you’ve really got the Mati, the ptoo-ptoo isn’t enough, nor are the tied-up knots that are supposed to protect you from it – the only way to cure it is to get help from a sufficiently qualified person in town, usually an older women. It’s a serious deal, and two of the diggers in our trench have had to get help from local women because of the evil eye – one of them was cursed by his own mother because she did not approve of his bride-to-be.

Katerina’s great-grandmother was, actually, one of the curse-removing women. Her family was from Farsala in Thessaly, and when Katerina was a little girl, all the 90 year-old people in town would fuss over her because she looked just like her great-grandmother, who was remembered to have helped a whole bunch of people. Great-grandmother was so effective, in fact, that people came from the neighboring towns to get help; she never charged money and was always successful. Katerina was told how the process worked – the woman said a prayer, the Our Father, over the afflicted person. It was repeated three times and then the woman said a certain phrase in which the name of the sick person was given and Mary was asked to get rid of the evil eye. Katerina thinks there must have been something else involved, too, but she was never told what that might be.

Not all the older women in Greece are nice and beneficient, though. Even here in Corinth some serious trouble has been caused by the malefactions of yia-yias (grandmothers). Corinth got a new priest some time ago, a younger man who was fairly progressive. During Easter week, when everyone fasts, the priest advised the yia-yias that it was okay if they did NOT fast, since they’re very elderly and frail, and it was damaging to their health. This advice was viewed as sacrilege and ended up pissing off a lot of ladies in black. I’ve heard from two different sources that the yia-yias in town put a curse on the priest – it seems you can tell a person is cursed when lots of terrible things befall them. The priest ended up having two sons: one was born with a mental disability and the other had some problem with his hand. The priest himself was in a car wreck and had various other misfortunes.

Tasos , our shovel man, told me about some more general stories about witches in our area. He said that, when they really want to curse someone, witches in Corinth go naked into cemeteries. Dancing in the night, they curse people by dropping bars of soap, pierced by nails, into wells.

It’s one thing to read about that sort of thing in antiquity, when you’re separated by the centuries. It’s another thing to hear about it down the street…that’s some spooky shit.

Monday, June 15, 2009

I want the gold

1) It's about people in a community coming together to celebrate imagination, to celebrate story-telling, to celebrate make-believe.

2) It's about people not taking themselves too seriously.

3) Everyone in it is a born showman.

4)It's all about an excuse to hang out with your neighbors on a warm evening, laughing.

5) It's folk-lore and fairy-tales in the city.

6) And yes, the Amateur Sketch.

Friday, June 12, 2009

The Well Strikes Back

But that was the first day when we were conscientious about removing the superfine silt. The second day? Not so much.

Apparently, the one water tank filled up with soil, then the second water tank did so, then the same in all the tubing business, and then, finally, the sieve just couldn’t take it anymore.

It exploded.

Guy (our director) and Thanos Webb (the bone dude), while innocently trying to clean out the machine for more mud bricks, got hit by a geyser of sludge that shot up, hit the underside of the umbrella, and rained back down upon them. I’m told they even tried to run away, but the volcano of mire actually followed them as they fled.

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

Dear Virginia, Merry Christmas

What's interesting about Christie, though, is that she was familiar with the life archaeological. The mystery author was lucky enough to work at the excavation of Ur and Nineveh, and her book Murder in Mesopotamia is set in an archaeological dighouse. In the 30s she married Max Mallowan, a British archaeologist who was even director of the BSA in Iraq. Christie wrote all about being part of an archaeological family in her book, Come, Tell Me How You Live - she had worked with her husband in the field, keeping notebooks and mending excavated pottery.

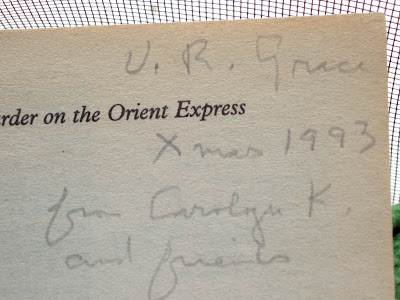

Like Loring Hall in Athens, Corinth has a few book shelves filled with novels left behind by visitors and more permanent residents. A few of those novels are by Christie, and I decided to go for the Orient Express because it was the most recognizable to me. When I opened up Christie's book, I saw this:

It's not uncommon to find names scrawled on the inside covers of ASCSA novels. Some of them, in fact, can go pretty far back, like this one from Doreen Spitzer:

Spitzer was a long time member of the ASCSA community and Trustee of the School. Cosy (her nickname) signed this book in 1966 and left inside a draft of a little rhyming poem, written as an introduction for the president of Bryn Mawr College.

Virginia Grace, who signed her Agatha Christie book one year before she died, is something of an archaeological celebrity (read her biography here). She first came to the American School in 1927, the same year as Lucy Shoe Merritt, with whom she became travel buddies. She ended up spending most of her life in Athens, and most of that would be dedicated to studying the stamps on amphora handles.

She collected drawings of the little stamps and catalogued over 25,000 of them...This may sound incredibly boring...In fact, apparently everyone else thought it WAS boring, since no one else came up with the idea to study them in such detail. Basically, Virginia Grace single-handedly started the specialized sub-field of amphora stamp analysis and typology.

But why the hell would anyone want to study them?

The amphora stamps tell where and when an amphora was made. Amphorae themselves are like the ancient version of wooden barrels, filled with wine, salt fish, olive oil, or some other trade good. They were stacked in the holds of ancient ships and sent all over the Mediterranean. They have become especially important for underwater archaeology; more often than not, although wooden ships don't always survive, their resting place on the seabed can be identified by clusters of amphorae. And thanks to Virginia Grace, archaeologists can date these shipwrecks by the amphora stamps .

Even at my very first excavation in 2001 I heard about a little old lady who had lived in Athens and collected notecards with amphorae stamps. At the end of excavation seasons archaeologists would bring Virginia drawings of newly excavated stamped-handles, so that she might add them to her notecard collection. For decades Virginia Grace was at the center of a social and professional network stretching out in all directions, extended by each archaeologist who looked at an ancient amphora thousands of miles away and immediately thought of her. She was an eternal hub at the center of a remarkable net, anchored down in the storeroom of the Agora excavations at Athens. (And yes, I know, she even inspired me to mix my metaphors.)

ASCSA picture of Virginia Grace in Turkey, WWII.

I heard a lot about Virginia Grace this year from women at the School, often during Loring Hall's long, extended 2-hour lunches, Mediterranean-style. Virginia was apparently a willowy, beautiful woman, meticulous and organized, who loved living abroad. In WW II she was one of many archaeologists to be part of the O.S.S., America's wartime intelligence service. She had an apartment in Kolonaki, where she hosted Sunday lunches for friends in the archaeological community. She also was a spark plug, prone to telling it like she saw it, with little patience for ridonkulous-ness. But she was nevertheless stalwart, and would even get you out of Greek jail if you happened to get arrested for trying to swim across channels patrolled by the Greek army...apparently. And she was loyal to the end - her fiancee died when she was still young, but she never remarried and, although she'd lived her whole life abroad, it was her final wish to be buried back in America at his side.

She died in 1994, at the age of 93, after being a member of the American School community for almost 70 years. Like many past members, her things are still part of the School's floating material culture. It's not just stuff like her billion ancient amphorae down in the Agora Museum, but other things, like that table on which she hosted so many Sunday dinners, now in another ASCSA apartment. And then there's Murder on the Orient Express, which I've finally read, thanks to some connection that Virginia Grace had with ancient Corinth's dighouse. Books seem to be an especially common way for past archaeologists to connect with the younger generation in these here parts. Whether it's the enormous book collection of Ida Hill and Elizabeth Blegen, or Doreen Spitzer's book of poems, or Virginia Grace's archaeological contemporary, Agatha Christie, I highly suggest picking up a book next time you hang at the School - you never know who you're gonna meet.

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

ROMULUS!

In The Neverending Story, the very existence of the universe disintegrates before The Nothing. Only Atreyu can save it, but while doing so he loses Artax to the Swamps of Sadness. It was heart-wrenching, and I’m not sure that I really ever got over this part of the movie, even as an adult.

So fantasy loves the epic. After all, there’s even a subgenre called epic/high fantasy.

Sci-fi isn’t immune either, with Asimov’s Foundation series or Herbert’s Dune saga being about as epic as you can get, spanning thousands of years, characters and cultures, with the latter mixing in some serious existential questions here and there for fun.

Also a fan of the epic-ness is the entire genre of metal. There’s no question that metal has always included mythical elements - plus its big 80s heyday coincided with the rise of Dungeon and Dragons (read more on metal and D&D here).

My favorite band in 6th-grade. And yes, I still think they rule.

While there actually is a subgenre called ‘epic fantasy metal,’ metal’s love and dalliance with fantastical and momentous themes shows up even in the art and songs of mainstream bands; it also positively saturates the more subgenre-oriented groups.

.jpg)

Ever popular in Tallahassee, Florida, land of my Master's degree.

So it makes perfect sense that metal has finally merged with the ancient epic. In particular, it has embraced one of the most famous and enduring epic stories known to us, the tale of the founding of Rome. Livy, the Roman historian of the late 1st century BCE, tells of the twins Romulus and Remus, exposed as infants and nursed by a she-wolf. Many accounts of twins or siblings end up with an insurmountable rift growing between them, oftentimes because one is good and the other is bad. Romulus and Remus seem to be relatively normal (if you count wolf-suckling as normal), at least up until they come into conflict over the foundation of Rome. Brother kills brother and, when all’s said and done, Romulus is the lucky guy to get a city named after him.

I’m not sure why this hasn’t happened more often, but lucky for us, there’s now a band out there called Ex Deo that has created a concept album about Roman history. It’s a death metal group that’s a side project of another band, but apparently they’re getting pretty popular among death metal connoisseurs. And it looks like, now that their new song about the 13th Roman Legion is out, even Italy is a fan. The lead singer recently said:

“Word of mouth has been spreading like wildfire worldwide about EX DEO at the moment! I didn’t think there were so many metal heads that were into the concept of the band and Roman history as much as I am. I was anxious to see the response of the people of Italy and Rome today and the media there has accepted us with open arms. Now with their seal of approval we can show the world ROME! [We have] another defiant track called 'Legio XIII.' It’s a song in honor of ROME's most devastating and lethal Legion ever assembled; the 13th Legion which helped bring Caesar to power.”

And so Roman epic becomes popular again. Hollywood tried to do the ancient epic it with Homer and Brad Pitt, but failed. Perhaps instead we can pin our hopes on Ex Deo. Check out the totally amazing video for their title track, ‘Romulus.’ For those without a death-metal-trained ear, the lyrics go along these lines: “Romulus, from the wolf's mouth, I feed eternity/ Romulus, with my brother's blood I opened wide the gates of time/ Standing at the hill cliff, a flock of birds crown me/ I am fathered by the god of war, I am the king of Rome/ Then his jealousy blooms, the envy to lead my people/ So perish everyone who shall leap over my wall!"

I can’t wait for the 13th Legion video!

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Method

Masters of the Well: Thasos, Panos the Elder, Panos the Younger.

Now, we may have closed the well, but its legacy lives on - piles and buckets of dirt, pottery, enormous quantities of bone, and what archaeology types call ‘small finds.’ To get that pottery and bone and stuff out, however, the soil itself has had to be processed in a variety of ways. Since many of you, oh friends, family,and readers, have not actually been on an archaeological site, I thought the well might actually prove an effective way to explain some of the things that go on hereabouts.

The well. Telos (‘finished’). If you look close, you can actually see my reflection taking the picture.

All the soil that came out of the well has to be dry sieved. That is, all the soil is shaken through a screen to separate the bits of stuff from the dirt This entails bending over in the hot sun for long periods of time, inhaling dirt. I highly recommend sweatbands on the forehead. The process also requires eagle eyes, as the whole point of dry sieving is to catch things that might have been missed when the dirt was first removed - this might be diagnostic pottery, small bones, egg shells, metal objects, glass, etc.

We also collect what is called a flotation sample from each section of the well. A flotation sample is basically a bucket of dirt that is taken to the water sieve, a fancy contrivance that allows archaeologists to collect organic remains.

.JPG)

All the dirt is poured into a screen that’s in the water – organic remains, like seeds or charcoal, float to the top and are rescued. But all the survivors have to dry before anything else can happen to them, so the little pile of organic stuff is hung out to dry, while the other leftovers, washed clean of dirt, are laid out on plastic.

Then the fun begins. The other residue (heavier material that doesn’t float, like rocks, shells, bones, roof tiles) has to be sorted into boxes according to their size, they have to be weighed, and their volume must be established (Gooooo Water Displacement!).

Sorting flotation material is precise work, done with tweezers, and is probably one of the more exhausting things we have to do; it’s a little hard on the eyes and the back, but its worth it when you get exciting treasures like fish vertebrae. You think I’m joking, but fish vertebrae are cool. Anyways, like I said, it’s rough work and, according to INSTAP’s awesome Archaeological Excavation Manual 1 (Retrieval of Materials with Water Separation Machines), it can best be accomplished by “students and other unskilled individuals (12)”!

When wells go out of use, they are usually filled up with garbage and junk to prevent unsuspecting infants or puppies from falling in; as they say, one man’s trash is another man’s archaeological treasure. That fill also helps date when the well went out of use. Most of it is dry soil; that is, it’s dry until you hit the water table. Then suddenly the buckets coming out of the well look a little something like this:

Processing this sort of thing becomes a bit more problematic, since it’s too wet to dry sieve and water sieving all of the context takes far too long. We tried laying some of it out to dry on plastic, but ran out of space. My trench partner, Marty Wells, suggested that we ‘water screen’ the mud. Water screening is basically dry sieving, but with a hose spraying water on the soil to wash the silt or mud through quickly.

Of course, bringing a little enthusiasm to the water screening process is equivalent to visiting Wet n’ Wild in the bayou; it’s all water and all mud and all splashing.

If you’re lucky, however, your excavation staff is crafty. And I mean that both in the intelligence sense, and in the arts and crafts sort of way.

Because then you get a lovely nylon dress to wear.