What's interesting about Christie, though, is that she was familiar with the life archaeological. The mystery author was lucky enough to work at the excavation of Ur and Nineveh, and her book Murder in Mesopotamia is set in an archaeological dighouse. In the 30s she married Max Mallowan, a British archaeologist who was even director of the BSA in Iraq. Christie wrote all about being part of an archaeological family in her book, Come, Tell Me How You Live - she had worked with her husband in the field, keeping notebooks and mending excavated pottery.

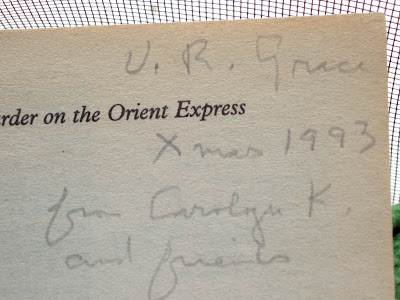

Like Loring Hall in Athens, Corinth has a few book shelves filled with novels left behind by visitors and more permanent residents. A few of those novels are by Christie, and I decided to go for the Orient Express because it was the most recognizable to me. When I opened up Christie's book, I saw this:

It's not uncommon to find names scrawled on the inside covers of ASCSA novels. Some of them, in fact, can go pretty far back, like this one from Doreen Spitzer:

Spitzer was a long time member of the ASCSA community and Trustee of the School. Cosy (her nickname) signed this book in 1966 and left inside a draft of a little rhyming poem, written as an introduction for the president of Bryn Mawr College.

Virginia Grace, who signed her Agatha Christie book one year before she died, is something of an archaeological celebrity (read her biography here). She first came to the American School in 1927, the same year as Lucy Shoe Merritt, with whom she became travel buddies. She ended up spending most of her life in Athens, and most of that would be dedicated to studying the stamps on amphora handles.

She collected drawings of the little stamps and catalogued over 25,000 of them...This may sound incredibly boring...In fact, apparently everyone else thought it WAS boring, since no one else came up with the idea to study them in such detail. Basically, Virginia Grace single-handedly started the specialized sub-field of amphora stamp analysis and typology.

But why the hell would anyone want to study them?

The amphora stamps tell where and when an amphora was made. Amphorae themselves are like the ancient version of wooden barrels, filled with wine, salt fish, olive oil, or some other trade good. They were stacked in the holds of ancient ships and sent all over the Mediterranean. They have become especially important for underwater archaeology; more often than not, although wooden ships don't always survive, their resting place on the seabed can be identified by clusters of amphorae. And thanks to Virginia Grace, archaeologists can date these shipwrecks by the amphora stamps .

Even at my very first excavation in 2001 I heard about a little old lady who had lived in Athens and collected notecards with amphorae stamps. At the end of excavation seasons archaeologists would bring Virginia drawings of newly excavated stamped-handles, so that she might add them to her notecard collection. For decades Virginia Grace was at the center of a social and professional network stretching out in all directions, extended by each archaeologist who looked at an ancient amphora thousands of miles away and immediately thought of her. She was an eternal hub at the center of a remarkable net, anchored down in the storeroom of the Agora excavations at Athens. (And yes, I know, she even inspired me to mix my metaphors.)

ASCSA picture of Virginia Grace in Turkey, WWII.

I heard a lot about Virginia Grace this year from women at the School, often during Loring Hall's long, extended 2-hour lunches, Mediterranean-style. Virginia was apparently a willowy, beautiful woman, meticulous and organized, who loved living abroad. In WW II she was one of many archaeologists to be part of the O.S.S., America's wartime intelligence service. She had an apartment in Kolonaki, where she hosted Sunday lunches for friends in the archaeological community. She also was a spark plug, prone to telling it like she saw it, with little patience for ridonkulous-ness. But she was nevertheless stalwart, and would even get you out of Greek jail if you happened to get arrested for trying to swim across channels patrolled by the Greek army...apparently. And she was loyal to the end - her fiancee died when she was still young, but she never remarried and, although she'd lived her whole life abroad, it was her final wish to be buried back in America at his side.

She died in 1994, at the age of 93, after being a member of the American School community for almost 70 years. Like many past members, her things are still part of the School's floating material culture. It's not just stuff like her billion ancient amphorae down in the Agora Museum, but other things, like that table on which she hosted so many Sunday dinners, now in another ASCSA apartment. And then there's Murder on the Orient Express, which I've finally read, thanks to some connection that Virginia Grace had with ancient Corinth's dighouse. Books seem to be an especially common way for past archaeologists to connect with the younger generation in these here parts. Whether it's the enormous book collection of Ida Hill and Elizabeth Blegen, or Doreen Spitzer's book of poems, or Virginia Grace's archaeological contemporary, Agatha Christie, I highly suggest picking up a book next time you hang at the School - you never know who you're gonna meet.

No comments:

Post a Comment